Design systems, Systems design and the wonderful world in between – Part I

by Joannes Vandermeulen [5 min read]

I first came across the terms “design” and “system” 17 years ago, when I started my bachelor’s degree studies and they haven’t left me alone ever since. In fact, I made a career out of them, mostly by juxtaposing their order in sentences.

My first degree was in Products and Systems Design Engineering. My second degree was in Service Systems Design. After my internship, Namahn sponsored my thesis on systemic design. I spent the last year designing a new course on design systems and consulting large organisations in their governance and adoption.

While working on the new design systems training course, I tried to collect insight about relevant content by asking people on our social media channels what they would like to learn about design systems. Several responses came back on what people would like to learn about systems (or systemic) design, rather than design systems.

People often confuse the activity of purposefully bringing change in social systems, systemic design, with the latest trend in organising assets and knowledge for digital product design and development, Design Systems.

Design systems have been advertised as the single source of truth for design and development, but for many organisations they can easily end up like an electric guitar hanging up on a wall; very beautiful to look at, but not quite what it was made for.

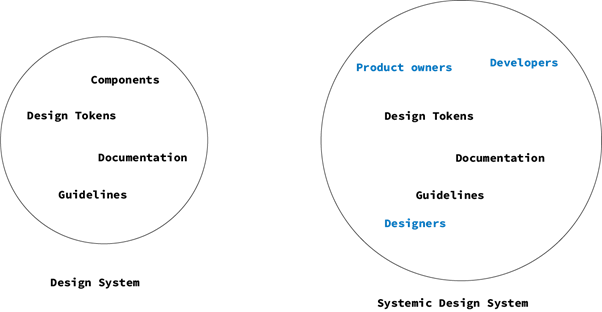

Systems are made up of their parts and the interactions between them, both actual and potential. Ask any design systems enthusiast about what design systems are made of and you’ll see their eyes shine as they talk about components and design tokens.

However, what makes design systems living, the parts that matter, are not beautiful chunks of code or components and tokens, but real, flesh and bone people. Design systems can easily end up as expensive wall decorations because the social aspect and complexity that comes along with it is often disregarded.

Seen from that perspective, the challenge of embedding a design system in an organisation becomes a problem of dealing with social complexity. It becomes a systemic design challenge. Turns out our confused social media followers were, in fact, quite advanced in their design systems thinking.

Systemic design systems

Systemic design comes with a specific mindset, vocabulary, theory and methods that we can leverage and play with while creating design systems that matter. It can help us to anticipate specific behaviour that will emerge and then proactively care for.

Design systems seen through a systemic lens have broader boundaries that incorporate humans and parts of content. All of the interactions between them are a design concern.

They are appreciated as dynamic; there is no final version of a design system. It is more relevant to talk about stable states and transitions between them. Planning becomes about understanding the delicate balances that make the system stable in its current form and identifying actions that will drive the system in a new, but still stable state.

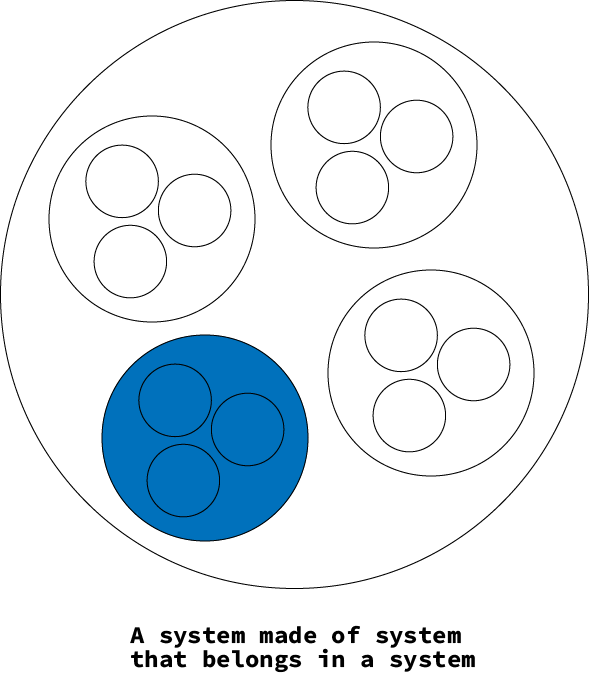

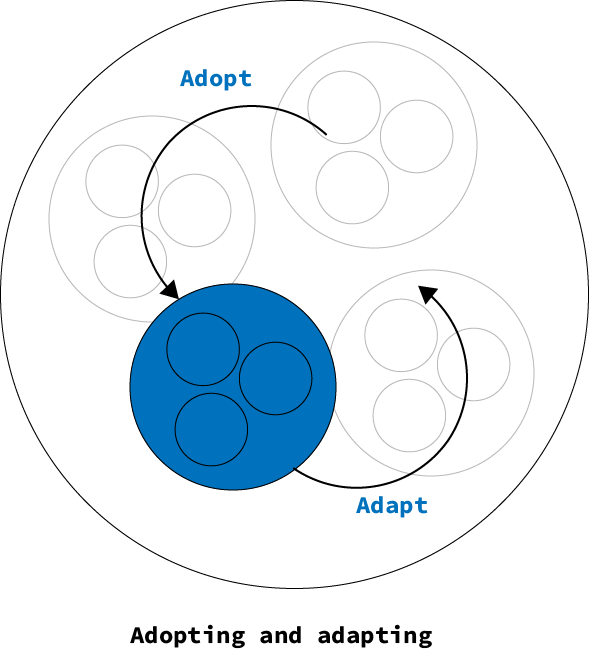

Design systems are part of systems and are made up of systems. The purpose of a design system is informed both from the outside-in and the inside-out. It should be a well-balanced mix between how the members of your design and development community want to evolve their practice and the expectations that are set from the outside environment. Either these are C-Suite expected ROI’s or global accessibility standards. The same goes with legitimacy that must be acquired in both directions. Both product teams, (the systems within) and stakeholders across the organisation (the systems outside) must recognise their value. In social systems theory, new systems juggle constantly between adoption (incorporating behaviours of external systems to fit within) and adaptation (trying to change the external systems to fit better).

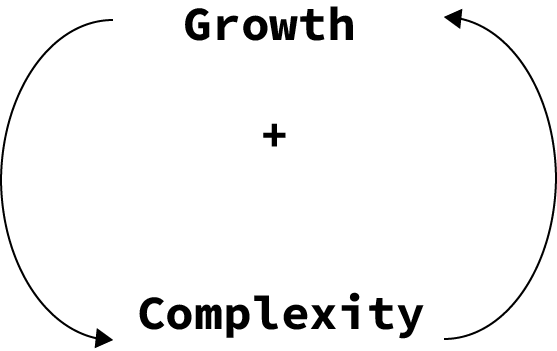

Design systems also become more complex as they grow (and they grow because they are complex). In the systemic universe, complexity and growth are locked in a causal loop like that of the chicken and the egg. A design system with four members can handle new additions to the component library in a single afternoon, but it will need more members to support a larger portfolio of applications. A design system with 50 members can probably handle the full portfolio of applications, but it will need to implement a process with clear steps, criteria, guidelines, roles and task distribution in order to handle new contributions.

Design systems will always have tendencies of self-organisation. While in general we recommend considering aspects of governance early in the process, we should also leave room for design systems to obtain their natural shape. Once again, with growth comes complexity. A design system will naturally evolve to more complex governance structures while it is growing in members and content. In reverse, as the Spotify story taught us, a design system unable to fit its context or work well with systems above and below, will probably de-evolve into simpler structures.

Design systems also have emerging properties and behaviours. This means that each design system is unique. Even if you re-use components and design language of one of the publicly available design systems like Google’s Material Design, it will still be one of a kind, because it will evolve into a unique context and include unique people. An example of emerging properties comes from the domain of language. Designers and developers in different organisations or even in different teams within the same organisation, will call the same components with different names. It is wise to get inspired by what is out there when we kick-off new design systems, but it is unwise to copy and try to enforce external meanings. Atomic design greatly inspired the design systems movement, but do the people in your team actually use the terms atom and molecule when they talk shop?

Design systems have leverage points; domains of intervention where action can evolve design systems from one state to another. One of the most potent systemic design thinking tools is the 12 leverage points introduced by Donella Meadows . It describes 12 types of interventions that bring change to systems, ranked by impact, from less to more. In the second part of this article, we are going to dive a bit deeper and examine the most relevant leverage points for design systems.

Posted on October 1, 2020.